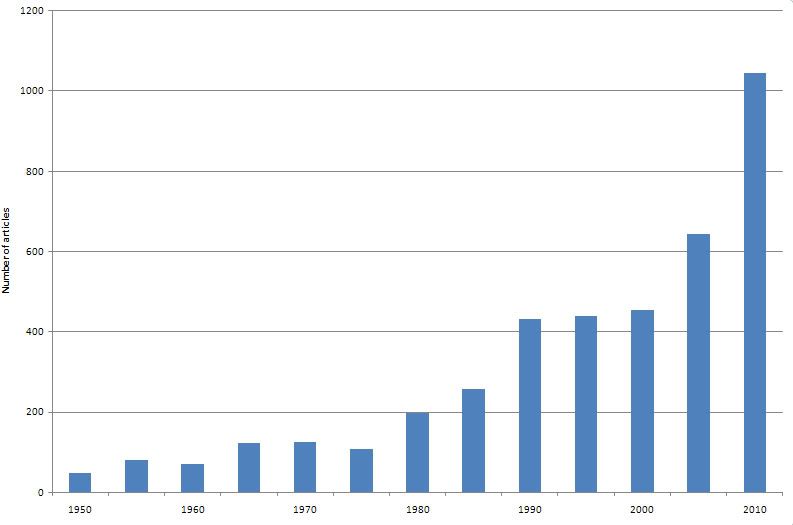

To start off we should look at how much research has been going on to date; a good way to judge that is by looking at the number of scientific journal articles that have been published on endometriosis over the last 60 years. Figure 1 below shows the number of scientific articles published on endometriosis since the 1950’s, and as you can see, there has been a surge in endometriosis research in recent times. To put it into context, there have been more articles published on endometriosis since the year 2000 than there were articles published in all the years preceding 2000.

Figure 1. Number of scientific articles published on endometriosis since 1950 (click image for full size)

So we appear to be living in a kind of ‘golden age’ of endometriosis research at the moment. Unfortunately though, whilst this has led to a better understanding of how the disease works, it hasn’t really translated to any dramatic improvements in the level of treatment for the disease, yet.

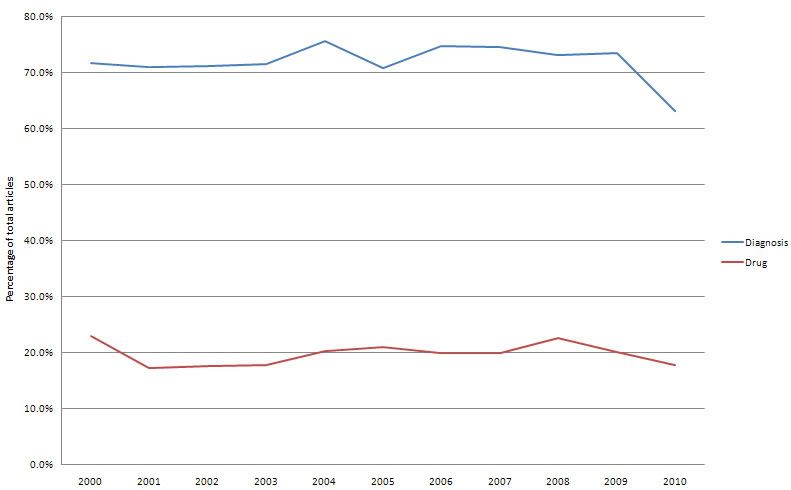

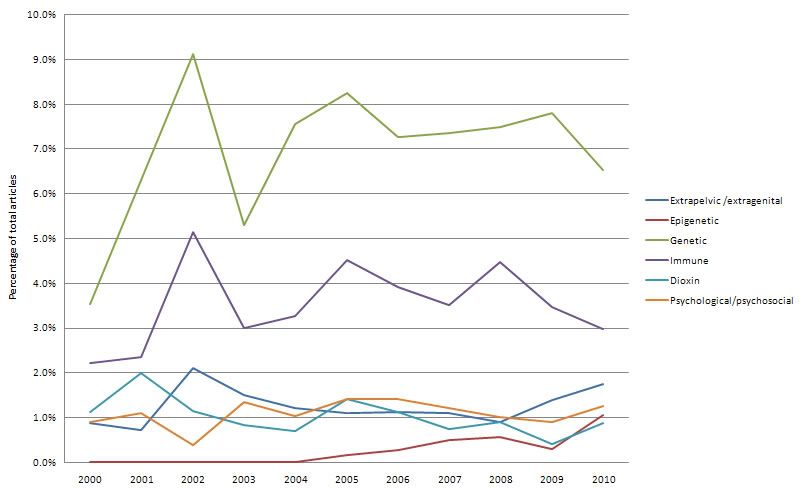

So what are the main subject areas being focussed on at the moment? Figures 2a and 2b show what subject matters are most common in the field of endometriosis research.

Figure 2a. Trends in endometriosis research (click image for full size)

Figure 2b. Trends in endometriosis research (click image for full size)

As we can see from Figure 2a the number of papers published with the keywords ‘diagnosis’ or ‘drug’ remained fairly constant with a dip around 2010. We’ll have to wait until the end of 2011 to see whether interest in these areas goes up again. It could be the reason for this dip in these areas is tied into the current global financial crisis. Drug research in particular is a very costly undertaking (it can cost nearly $1billion just to take one drug from concept to pharmacy shelf); these days drug companies are unlikely to be forthcoming with the hundreds of millions of dollars necessary for research into drug treatments for endometriosis. That said, articles with the keyword ‘diagnosis’ still dominate the research landscape comprising around 70% of all papers published on endometriosis. This reflects the desperate need for better diagnostic methods for endometriosis which, given the large amount of interest in the subject, will hopefully yield some results soon.

There has also been a steadily increasing level of interest in genetic and immune system research into endometriosis. With the completion of the human genome project at the turn of millennium, looking into what genetic differences make us more or less susceptible to certain diseases has become steadily easier and cheaper, so there’s no surprises there. What is quite interesting is the emergence of epigenetic research into endometriosis around 2005. Epigenetics is a relatively new field of science, only really being properly investigated from around 20 years ago. The difference between genetics and epigenetic is that, whereas genetics is concerned with the changes in the code of DNA, epigenetics is concerned with changes in the bits that are attached to the DNA. These epigenetic marks control which genes are turned ‘on’ or ‘off’ in your body and are therefore essential in maintaining correct bodily function. Several studies have shown that a number of the epigenetic marks are altered in endometriosis and this may provide some interesting answers to some of the more puzzling aspects of the disease.

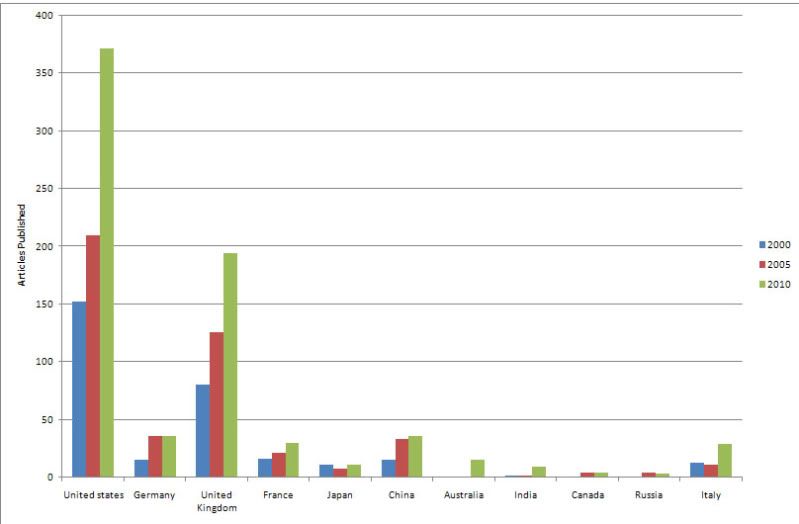

So, the final thing to consider is where this research is coming from. Unfortunately, there is no easy way to know exactly as the current search engines for scientific literature don’t let you search by the location of where the research was done. I could go through the 17,000 individual articles on endometriosis and note down where the research centres were, but I don’t think I’ll live that long. What the current search engines do allow you to do is search by where the articles were published. The trouble is, where a piece of research was carried out and where it was published could be two completely different places. I could write an article here in England and get it published in an American journal and the search results would show that the article was American. Nevertheless this information does provide some interesting insights into where the major centres of endometriosis publication are (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3. Articles published on endometriosis by country of publication (click image for full size)

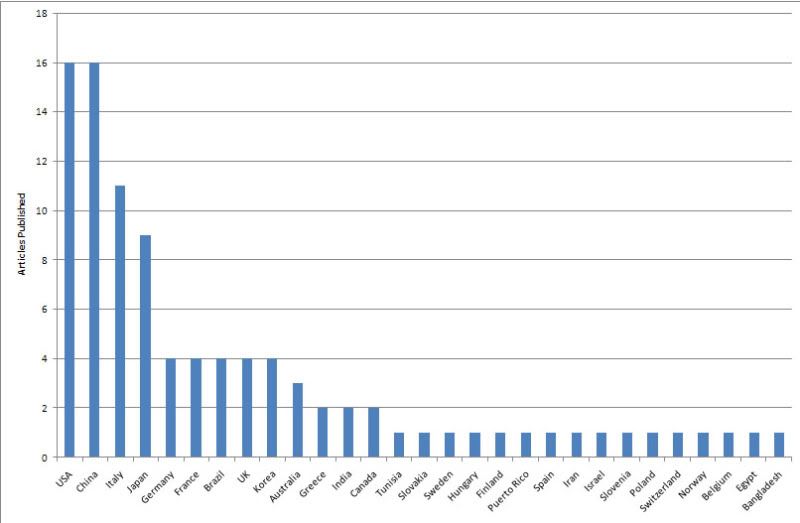

Unsurprisingly the majority of endometriosis research is published in America and the UK; this is most likely due to the fact that if you want to get your research to a wider audience, English is the most widely spoken language in the world, so it’s better to have it published in an English language journal. The most important thing to see in this data though, is that all the bars point upwards over time, meaning more research into endometriosis. To emphasise my point, let’s look at the last 100 articles on endometriosis (between 13th June and 18th April 2011) by the country in which the research was actually done. Figure 4 below shows that there is a huge diversity of countries in which endometriosis research is being carried out, just within the last few months.

Figure 4. Articles published on endometriosis by country of research (click on image for full size)

Unsurprisingly, we can see that the most research is coming out of the superpower countries like the USA and China. Whilst Figure 4 only shows the results from 100 articles it still tells us that endometriosis is being addressed as a global problem and that the world is standing up and taking notice.

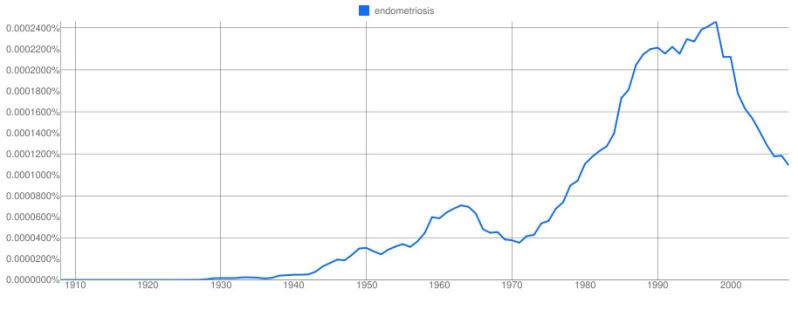

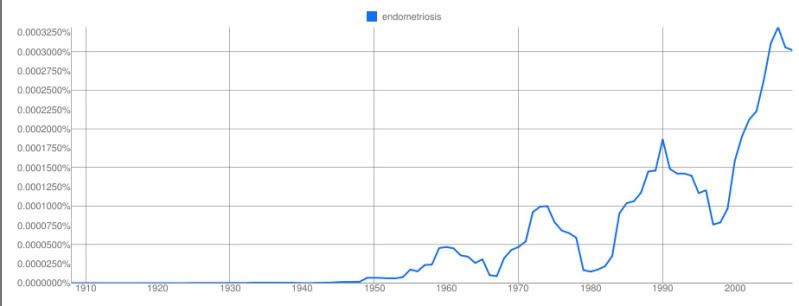

But we don’t need to only consider the scientific literature published on endometriosis. There is a handy little feature of Google Books called the Ngram viewer that lets us look at the number of books published on endometriosis over the last 100 years of so. If we look at Figure 5a and 5b we can see that during the period after 1960 the number of books concerning endometriosis really started to flourish. Sadly though the amount of books published in American English has taken a downturn (Fig.5a). On a positive note though, books in British English have continued to increase at a fairly constant rate (Fig.5b) and fortunately, for the most part, you don’t need to translate between the two English forms.

Figure 5a. Books published on endometriosis in American English (click image for full size)

Figure 5b. Books published on endometriosis in British English (click image for full size)

Sometimes it can feel like the world is ignoring those who suffer with endometriosis, but that really is not the case, as I hope I’ve shown here. I wouldn’t go as far to say that the behemoth of scientific research has its attention fully on the subject of endometriosis, but the great beast definitely has one of its eyes cast over endometriosis and is slowly realising its importance. If the current trends that we have explored here continue then the future for endometriosis sufferers doesn’t look so bleak. That’s an important notion to bear in mind, when your daily life consists of so much suffering, you must believe that it will get better, I certainly do.